JF Books Returns

The rise and fall of an independent bookstore and the fate of civil society in China.

In the restrictive environment of China, Shanghai’s iconic Jifeng Bookstore, with its high-quality selection of humanities and social science offerings, embodied resistance, defiance, and an indomitable spirit. When Jifeng was forced to close in 2018, the fate of one bookstore became a symbol of how public life in China had been strangled. With its relocation to Washington, D.C., and its rebirth as JF Books in September of this year, the spirit of Jifeng continues its mission to “live in truth” through free expression and the pursuit of a normal, orderly life in community with others.

By Jiang Xue | First published by the Chinese-language news magazine Wainao | Translated by Probe International

As dusk came, Miao Yu waved goodbye to the last group of readers and stepped out of the bookstore, while his wife, Xiaofang, locked the door behind him. The lights along Connecticut Avenue flickered on, and the Chinese characters for “Monsoon” (Jifeng) stood out, outlined in fine neon lines, glowing amidst the surrounding English signs.

It was September 1, 2024, and Jifeng Bookstore had reopened in the heart of Washington, D.C. as JF Books, six and a half years after being forced to close its doors in Shanghai.

The first day of business was unexpectedly lively, with a steady stream of visitors from morning until night. Now, after closing, the excitement still lingered in everyone’s eyes. Miao Yu invited his three young employees for a meal at a favorite Chinese restaurant. As soon as they sat down, the kind-faced owner approached with a glass of wine for Miao Yu. Also from Shanghai, the owner knew about the bookstore’s reopening and was happy for him.

At 11 a.m. that morning, the bookstore had officially opened. The scent of fresh flowers mixed with the “fragrance of books,” and the two-floor space, though less than 200 square meters, was packed all day. Miao Yu stood in the store, greeting the many visitors who recognized him from a video that had circulated online—of him giving a passionate speech on a table the night Jifeng was shut down in Shanghai. That speech left a long-lasting impression, so many people knew who he was.

Over five hundred books were sold on the first day, far exceeding Yu’s expectations. While his team was excited, Yu himself remained calm. “Honestly, whether we sold one book, twenty books, or hundreds today, my mood wouldn’t have changed much,” he said.

It was as if fate had guided him to this point, as if this was his “must-do mission.” Miao Yu had thought that his chapter of the Jifeng story was over for good, but a casual conversation with a friend at the end of 2023 sparked an old desire—perhaps Jifeng could rise again. Once that thought took hold, there was no stopping it. He realized that on January 31, 2018, during the bookstore’s final night in Shanghai, when plainclothes police stood outside while readers with passion still gathered inside, the flickering of the candlelight of hope in the store had never truly been extinguished in his heart.

For his friend, Yachuan Shen, who had known Miao Yu for a long time, the entrepreneur was always someone with a “strong motivation to take action.” This time was no different. By early summer 2024, Yu had signed a lease, securing a new place for Jifeng Books in this city [not just any city, but the U.S. capital] on the Atlantic coast. And not just any lease—a ten-year contract. Another friend, L, who marveled at his determination, was surprised. “Everyone knows this is not the time to open a bookstore, let alone a serious Chinese bookstore in the U.S.—and to sign a ten-year lease?” It was clear to all how determined Yu was.

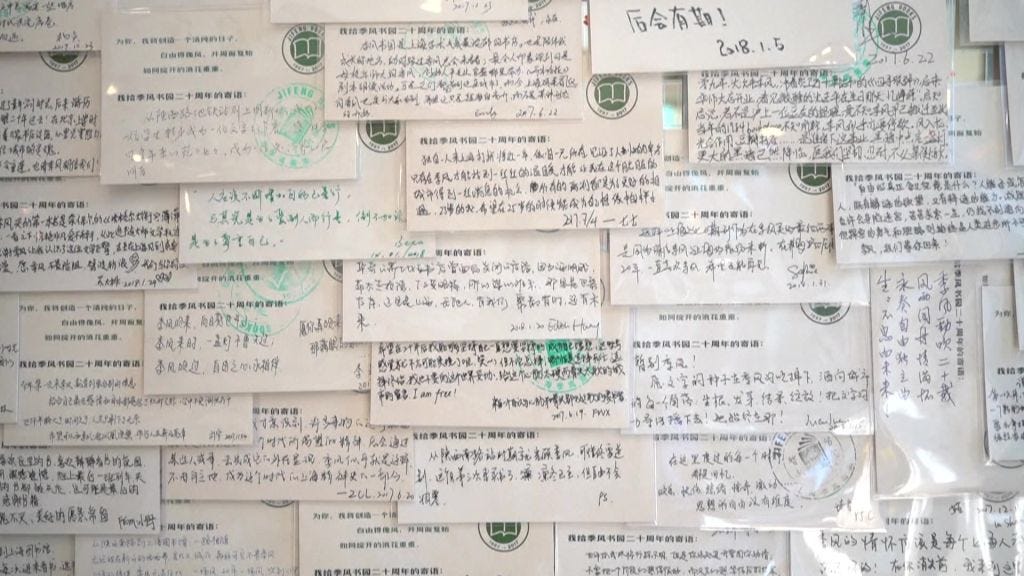

Located in an old building on Dupont Circle in downtown Washington, JF Books has a modest, unassuming appearance. As one reviewer on Google Maps noted, it’s “not big, but charming.” Upon entering, visitors are greeted by tall bamboo-made shelves filled with thousands of Chinese and English books. The bookstore also features a plaque reading “Jifeng Bookstore,” inscribed by the writer Gao Ertai. Perhaps the most eye-catching feature is the large wall mirror, covered with over 200 notes left by readers when the Shanghai store closed in 2018, which had been carefully brought across the ocean to this new space.

“The wind continues to blow, and its name is freedom.” This note, left by an anonymous reader outside Jifeng at the end of 2017, now seems prophetic. Today, the bookstore’s logo is, “The wind speaks, calling for freedom,” and it is printed on the custom tote bags for sale in the store.

Jifeng Bookstore was once a window into China’s civil society. Now, that vibrant era has long passed. Over the past six years, Miao Yu himself has endured the closure of his bookstore, his departure from China to study abroad, his wife’s travel restrictions, and his eventual forced exile. Through the changing seasons and difficult times, Jifeng has found new life, now blowing once again—this time, outside of China. This is not just the story of a bookstore’s fate but a reflection of the twenty-year journey of civil society in China.

In the first half of 2017, Miao Yu traveled between districts in Shanghai, hoping to find a new location for Jifeng. Early that year, he received notice that the Shanghai Library, where Jifeng’s flagship store was located, would not renew their lease when it expired on January 31, 2018.

The official reason seemed legitimate, but Miao Yu and the government officials involved were well aware of the unspoken truth: Jifeng had been labeled by top Shanghai officials as a “frontline of liberalism” and a “hub for color revolution,” targeted for elimination. Unlike the two earlier “Defense Jifeng Store Battles” in 2008 and 20111(sparked by operational issues),2 this time the political winds had shifted and the closure of Jifeng seemed inevitable.

Still, Miao Yu wasn’t willing to give up. During that time, he searched every district in Shanghai for a potential new home for Jifeng. The bookstore’s reputation was strong, and several companies expressed interest in collaborating. But as soon as Yu left their offices, the phone calls would come: “We’re sorry, but we’ve received an official notice—we cannot work with Jifeng.”

Another branch of Jifeng, located in a community store that partnered with a café, was accused of “selling books without a permit.” When they applied for an official “book business license,” their application was ignored, and the store was eventually shut down by force.3 Cooperative projects partnered with other local stores in areas like New Jiangwan, Balitai, and Jiading District all fell apart under government pressure.

With the closure inevitable, all that was left was to organize a dignified farewell—a graceful “funeral” for the bookstore. This was also the wish of Jifeng’s founder, Bofei Yan. But deep down, Miao Yu still held on to hope for a new beginning. He once said, “In the process of dying, there is also the possibility of new life. Let’s see if there is any way to continue our original vision.”

In 2017, the year the closure was announced, Jifeng was celebrating its 20th anniversary. To mark the occasion, the bookstore planned a series of events titled “Twenty Years of the Jifeng Era,” organizing twenty lectures on humanities to talk about the key cultural themes and social issues of each year.

This was characteristic of Jifeng’s spirit. In the five years since Miao Yu took over the bookstore in 2012, Jifeng had hosted over 800 events, including a series of cultural lectures. Fearing official interference, announcements for some lectures were only made the day before, yet they still managed to draw hundreds of attendees. It was almost miraculous.

But that miracle was about to be interrupted—a metaphorical sword, long hanging in the air, was now poised to drop mercilessly.

At this pivotal moment, Miao Yu decided to maximize the bookstore’s role as a public space. If fate could not be altered, he would ensure that Jifeng left a lasting echo in Shanghai. Despite the constant disruptions, Jifeng’s activities became more frequent.

Snow piled up along the streets, and Shanghai was approaching its coldest days. Since the farewell announcement in the spring, readers from across the city, and even the country, had been visiting daily, leaving notes—some even in tears. In December 2017, Jifeng hosted an event to discuss the fate of independent bookstores in China, including its own. The guests included three representatives of China’s independent bookstores: Bofei Yan, Suli Liu, and Ye Xue. Suli Liu was the founder of Beijing’s All Sages Bookstore, and Ye Xue had started Guizhou’s Sisyphus Bookstore.

The event was a dialogue that reflected on the fate of independent bookstores in China, which was, in fact, also the fate of civil society and liberalism in the country. Ye Xue spoke with deep emotion, going so far as to say, “The death of Jifeng is of such importance. Anyone who doesn’t take part in this farewell cannot be called a reader in China. Jifeng gave people an opportunity to define who they are and what they stand for.” His words, though extreme, carried profound meaning in that moment—Jifeng’s closure was not just the fate of one bookstore but a symbol of the public life being strangled in China.

The long goodbye continued, and Miao Yu had to deal with the many mundane tasks that came with the “death of a bookstore,” including clearing out inventory and taking care of the employees. One day, while inspecting the store, he discovered several hidden surveillance cameras that had been secretly installed without his knowledge.

Once again, a group of police officers, part of Shanghai’s national security branch—essentially thought police—came to meet Yu at a nearby hotel. As the conversation was ending, Yu asked them, “Do you truly believe that what you’re doing—shutting down a bookstore like Jifeng—is the right thing to do?”

One of the more intellectual-looking officers responded, “You can imagine this as a scene from Orwell’s 1984.”

The countdown of 283 days was coming to an end. January 31, 2018, marked the final farewell. Plainclothes police stood outside as readers came from all directions to say goodbye. Inside the bookstore, people sang and read poetry. Miao Yu and the staff recited Keats’ Ode to a Nightingale. Music filled the air, candles flickered, and after the previous night’s disruption to the store's power, the atmosphere reached its emotional peak. Miao Yu climbed onto a table and began to speak:

“If Jifeng’s twenty years in Shanghai left anything behind, I believe it is a sense of purity—the purity of an independent pursuit of thought and truth, initiated by ordinary people. It gave us strength and courage. But it also left a scar. And in that scar, you can see ignorance and absurdity. This scar has formed, and it won’t heal. All we can do is transcend it. I look forward to the moment of transcendence.”

“The scar has formed, and all we can do is transcend it.” Six years later, that line is still remembered by many.

Six and a half years later, in September 2024, during the second week of Jifeng’s reopening in Washington, D.C., Miao Yu stood outside the store one warm autumn afternoon, smoking. A polite young man approached, holding a stack of newly purchased books. “You’re Miao Yu, right? I just wanted to tell you, I was one of the volunteers at Jifeng the night it closed,” the young man introduced himself in a calm, gentle voice.

He opened his phone and showed Yu a photo from the bookstore’s last night. In an instant, the memories of the lights, the songs, and the resilient spirit of that winter night came rushing back. This encounter, six years later, brought tears to Yu’s eyes. After shaking hands and saying goodbye, Yu learned that the young man had driven five hours from Duke University just to visit the bookstore.

“Jifeng Bookstore is like its name ‘monsoon,’ is like an ocean current, alive and ever-changing with the climate, much like the fate of modern China. Since leaving its traditional society and beginning the process of modernization, China has had to continuously absorb, resist, transform, and adapt to the outside world. This has become its destiny.”

In 2008, during an interview with Shanghai Xinmin Weekly, Bofei Yan once said these words. At the time, Jifeng was facing its first closure due to immense financial pressure. Back then, the environment was more relaxed, and there was still room to maneuver. Yan gave several interviews to the media.

Born in 1954, Bofei Yan represented a typical intellectual of his generation. He was 12 years old when the Cultural Revolution broke out. In 1969, he was sent to the countryside in Inner Mongolia as part of the zhiqing (educated youth) movement, where he spent six years, even serving as a production team leader. There, he witnessed peasants using Mao’s “supreme directives” as window coverings and saw how public ownership led to poverty and crushed everyday life. Beneath the façade of “socialist public ownership,” it was among the last remnants of private enterprise that kept people going. The Biao Lin Biao incident of 19714 marked his political awakening. After Lin’s death, the Central Committee circulated the “Project 571 Outline”5 for criticism, which became a key text for Yan and his generation of zhiqing—a shocking revelation that “pure politics didn’t seem to exist”6 even in the sanctified halls of Zhongnanhai.7

In 1987, after graduating from university, Yan was assigned to work at the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences. Shortly afterward, the famous 1989 Tiananmen Square Protest occurred. By the 1990s, as Deng Xiaoping’s southern tour began a national trend of entrepreneurship and commercialism, Yan left his government position. He first started a newspaper, then founded Jifeng Bookstore in 1997, which, at its peak, had eight branches. The popularity of Jifeng would go on to spread through Shanghai for 20 years until its permanent closure in 2018.

As an independent bookstore, Jifeng was known for its carefully curated selection and high academic standards, with a focus on books about the humanities and philosophy. Curating this collection was Yan’s expertise. After handing Jifeng over to Miao Yu, Yan stepped away from the daily operations and went on to establish Sanhui Publishing, which published high-quality books on humanities topics.

One of Yan’s goals for Jifeng was to carry forward the legacy of the Enlightenment ideals of the 1980s8 (as reported by Caixin’s journalist Haitao Xie in “Using Bookstores to Continue the Enlightenment Ideal”). In fact, many of the founders of independent bookstores in China during the 1990s were driven by the same idealism. Suli Liu of All Sages Bookstore, for instance, was imprisoned and lost his government job following the 1989 Tiananmen protests. Bofei Yan recounted how, in 2003, Wei Wang, founder of Beijing’s Feng Ru Song (Wind Into Pine) Bookstore, bought 2,000 copies of the Selected Works of Heidegger published by Sanlian, declaring, “If I sell 200 copies a year, I can sell them all in ten years.” That was nearly reckless idealism. Yan, however, reminded himself not to follow suit, emphasizing the need to control costs (as reported in the 2008 Xinmin Weekly article).

After weathering the operational crisis of 2008, Jifeng caught a brief respite but still struggled. By 2012, the bookstore was on the brink of closure due to financial difficulties across the industry. Yan decided it was time to find someone more suited to take over Jifeng—not for profit, but simply to keep the bookstore alive. Through a friend, he met the young Shanghai entrepreneur, Miao Yu. “At first sight, I knew he was a good, honest person,” Yan later remarked in an interview. He immediately offered the bookstore to Yu, who, without hesitation, agreed to take it on. At the time, Yu had no idea that this decision would profoundly shape his future.

Yu’s passion after taking over Jifeng surprised Bofei Yan. To allow the bookstore to operate smoothly and avoid raising government suspicion, Yan distanced himself from Jifeng and remained silent—an unavoidable sacrifice. But what Yan hadn’t anticipated was that, under Yu’s leadership, Jifeng would go even further in transforming from a bookstore into a public space. Jifeng had always hosted various reading events, but starting in 2013, lectures and activities became much more frequent. Many of the speakers were scholars aligned with China’s broader liberal movement.

During a long conversation in 2023, Miao Yu reflected on how Jifeng selected scholars for these lectures. “There were two criteria,” he explained. “First, the speaker needed solid academic credentials, someone who didn’t conform to outdated ways of thinking. Second, they had to have the courage to express themselves in the public sphere. The content of our discussions always fell into two categories: either helping us understand the reality we face or exploring the paths forward. Our discussions weren’t confined to ivory towers.”

In China, scholars who met these criteria were rare. They were more aligned with the concept of “public intellectuals.” However, beginning around 2013, the term “public intellectual” was increasingly stigmatized in Chinese state media, to the point where it became almost a derogatory term.

Guided by this intellectual ethos, Jifeng transitioned from a bookstore into a public social space. However, this shift coincided with the end of a brief liberal trend in China and the impending suppression of its already fragile civil society. More and more events were canceled by the authorities. In 2016, lectures by Jian Hao, Chu Zhao, Guoyong Fu, and Quanxi Gao were shut down, and in 2017, talks by Zhiwei Tong and feminist forums met the same fate.

According to Miao Yu, there was a brief “honeymoon” period between Jifeng and the Shanghai authorities. In 2013, during Yu’s first year running Jifeng, the bookstore even received cultural subsidies for private bookstores and was given a prime location at that year’s Shanghai Book Fair. But by the following year, the atmosphere had changed. When Yu reapplied for the subsidy, he could sense that Jifeng was unlikely to receive it again. He asked the official in charge if there was any hope. When the official shook his head, Yu dropped the matter. That year, Jifeng was given a barely passable booth at the book fair, and in subsequent years, none at all.

Without Yan Bofei, Jifeng didn’t shrink back—it seemed to step forward with even more resolve. The authorities quickly noticed this and labeled Yu Miao as “arrogant and unyielding,” meaning he was someone who couldn’t be easily changed. This was true—although Yu was young, his idealism burned as brightly as Yan Bofei’s, even though he always regarded Yan as his spiritual mentor.

When Jifeng’s commitment to the spirit of the humanities began to be regarded by the authorities as a form of “resistance,” its fate was determined. By 2017, the invisible sword above the head finally dropped. In a city as vast as Shanghai, there was no longer a place for Jifeng. What followed was a long farewell—a metaphorical curtain closing on an era.

In China, liberal intellectuals were deeply influenced by former Czech President and playwrighter Václav Havel’s idea of “living in truth.” Miao Yu, immersed in the process of civil society’s development, was no exception.

Miao Yu once said, if a bookstore had a personality, Jifeng’s would be one of “pursuing truth,” coupled with a spirit of defiance. Jifeng wasn’t an ivory tower focused solely on academic debates; it enthusiastically engaged with reality, tackling “one tough issue after another.” The bookstore had a special “film” section where it screened dozens of documentaries. Almost every major independent documentary filmmaker in China over the past few years had shown their works at Jifeng.

“These excellent documentaries, filled with the directors’ sincere emotions, told real stories of our times,” Yu reflected in 2020 in his essay, “The Vanishing Jifeng.” “But the manifestation of this ‘truth’ has become increasingly difficult in today’s environment. Those in power aren’t foolish; they know that the power of truth can break through anything, which is why they try to obscure it. But common sense tells us that ‘truth’ won’t disappear—it will only accumulate more life in the silence.”

“Jifeng’s stance wasn’t there from day one—it formed gradually, naturally growing from the stances of the people behind it,” said Bofei Yan, Jifeng’s founder. That’s why he summed up the bookstore’s identity with a single phrase: “An independent cultural position, free expression of thought.”

In 2024, when Jifeng reopened in the U.S., this phrase was printed on one of its custom book bags. A photo from Jifeng’s earlier days in Shanghai now hangs on the bookstore’s walls. As readers ascend the stairs, they can see how the bookstore, once a hub of intellectual exchange, drew in those who cherished freedom.

Miao Yu was born in Jinan, Shandong, on May 12, 1972. The Cultural Revolution was in its final stages but not yet over. He grew up in a warm household. His father was a professor of electrical automation systems at a university, and his mother worked as a technical editor at a television station. In his eyes, his parents were upright people. “If there was a fight on the street, they’d definitely step in to stop it,” he recalled.

In May 1989, as a high school senior, Yu watched as university students in Jinan organized protests. He and a few classmates sat on the wall of their school, Jinan No. 2 High School, watching the students shout out their demands. Like many Chinese people at the time, he was glued to the TV, watching footage of protests across the country and the hunger strikers in Tiananmen Square. It was a moment that stirred everyone’s blood. But after the military crackdown on June 4th, state-run CCTV began broadcasting messages labeling the students and citizens as “rioters.” From that point on, Miao Yu no longer believed in government propaganda.

In September 1989, Yu enrolled at Shanghai University of International Business and Economics. Among his classmates were Wen Kejian (who later became an economist) and his wife, Xiaofang. At the time, China was still reeling from the shock of the ruling party opening fire on its own people. Ideological pressure was high, and nearly all universities mandated military training for students, with drill instructors teaching obedience as the primary lesson.

The atmosphere at the university was stifling, but Miao Yu, with his artistic temperament, quickly formed several student clubs—a literary society, a guitar club—and even invited outside guitar teachers to give lessons. He also sought out professors from Shandong University to give talks on campus.

June 4th, 1990 marked the first anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre, and the sorrow was still fresh. Yu and seven or eight members of his literary society lit candles and held a memorial on the second floor of the school cafeteria. Security guards came and yelled from downstairs, eventually driving them away. But Yu still remembers the glow of the candlelight in the darkness and the suppressed passion of that night. “Even today, I can still feel it on my skin,” he said.

At the time, some of the seniors who had participated in the 1989 protests were graduating, and their job placements were severely affected. Two of the protest leaders were assigned to remote parts of Sichuan, and another went to Beijing. Both died young—whether from foul play or despair was unclear, but their deaths left a profound impact on the younger students. Yu described it as a moment when “we glimpsed a terrifying reality—a huge, dark force was lurking, but we couldn’t touch it. We couldn’t denounce it, and we couldn’t openly talk about it.”

Back then, International Trade was a hot major in the universities. After graduating in 1992, Yu was assigned to a state-owned foreign trade company in Beijing, hoping to eventually return to Shanghai and reunite with his girlfriend, Xiaofang, who later became his wife. Three years later, in 1995, he quit his job to start his own business. At the time, Bofei Yan had not yet left his post to establish Jifeng, though both men were in Shanghai and unaware of each other.

Yu recalls those early entrepreneurial days, pedaling a bicycle to malls to promote his products, struggling even to rent an office desk. After enduring the usual challenges of launching a business, he eventually found his footing and achieved modest success. In 2006, he participated in the “Xuanzang Road” Gobi Desert Trek Challenge with the Shanghai Jiao Tong University EMBA class, never imagining that this would be the beginning of his journey into the nonprofit sector.

The 2008 Sichuan earthquake became a turning point. That year also marked a watershed moment in the development of Chinese civil society. Seemingly by chance, countless lives were changed by the events of that year.

When the earthquake struck, Yu was in the Gobi Desert. One year earlier, on May 12th, his father had passed away—a date that was also Yu’s birthday. A year later, the grief had not yet subsided. Standing amid a natural disaster in 2008, especially in the desolate sands of the Gobi, he felt an even greater emotional impact.

While in the desert, Yu and his fellow trekkers—most of whom were young entrepreneurs—made a pact to dedicate themselves to disaster relief in the future. They immediately put this pledge into action, forming a volunteer rescue team at once when they were in the desert and undergoing formal training. By June of that year, they were in Yingxiu, Sichuan, transporting supplies to earthquake survivors.9

By 2011, when another Yushu earthquake occurred in Sichuan, this time in Yushu, Yu and his team had become a well-trained rescue force. They flew to Sichuan at the earliest opportunity, only to have their flight canceled. Undeterred, they flew to Xining instead, then drove for more than ten hours on mountain roads, becoming one of the first civilian rescue teams to reach the disaster zone. Afterward, they were present at the relief efforts for the Ya’an and Ludian earthquakes, which followed in 2013 and 2014 year, as well.

In disaster zones, problems are immediate and tangible. How do you use life detectors? Dig with your hands, or use shovels and small tools? How do you bandage the injured? How do you make a small stretcher? These are all concrete, practical matters.

“At the scene, all emotions are locked in the present moment. When you start asking questions about underlying causes behind the significant casualties in the earthquake and those graveless lives, that same courage transforms into the strength needed for on-the-ground rescue efforts,” Yu explained. By then, he had become a father. “Having a child makes you especially sensitive to the suffering of children. Seeing a child get hurt is unbearable for me—that’s the softest part of my heart.

“As members of society, we have a responsibility for the upbringing of children. Once you see the problems, you can’t look away,” he said. It was this belief that prompted him to turn his attention to helping more children and eventually become involved in educational philanthropy. He co-founded the Gobi Friends Public Welfare Foundation, launched the Baige Volunteers Trail, and established both long- and short-term volunteer teaching programs to help children in remote areas of Yunnan and Guizhou. He visited Guizhou every year, most often to Weining County in Bijie, one of the poorest counties in the region, roughly the same size as Shanghai but mostly mountainous. He traveled to most of the towns and schools nestled deep in the mountains.

How could these children have access to better education? Focusing on the educational philosophies of principals, he believed, was the best way to benefit children. Through a program that targeted rural school principals, Yu sought to help them reflect on what a good education really meant and how to act within the limitations they faced.

The training sessions were unique—principals participated in four days of intense trekking in the Gobi Desert. When they were out there, between the vast sky and the barren earth, their minds opened. That’s when the instructors would begin their lectures, helping the principals to explore the meaning of “people-centered” education. In 2017, for example, historian Yi Lei gave a lecture titled “The Awakening of Humanity in Modern China,” legal scholar Jianxun Wang taught “The Responsibility and Mission of Scholars,” Yuan Gu spoke on “The Life of an Observer,” and Xiaoyu Wang led a discussion titled “In the Midst of Storms, the Music Goes On.” These lectures offered rural principals a new window into life.

Xiaoyan Liang, a long-time advocate for educational philanthropy, came into frequent contact with Miao Yu during this time. “I noticed a deep intellectualism in him—one that sometimes surpassed his identity as an entrepreneur,” Liang recalled. In 2016, Yu invited her to give a lecture to the “Good Principals” in the Gobi Desert. “Unlike others who see philanthropy as just doing good deeds or needing to produce measurable results,” said Liang, “he was always contemplating how to create a better society. For example, by nurturing principals and shaping their ideas, he hoped to influence the entire education system.” Over the years, Liang, who had dedicated herself to educational causes, found Yu’s approach refreshing and surprising.

“In the end, one must seek light while journeying through darkness. Compassion, persistence, death, and resistance under the banner of humanistic spirit will surely plant seeds, silently enriching and awakening our lives.” In February 2019, Yu Miao wrote these words in his speech for a talk hosted by Harvard Salon.

At that time when he delivered the speech in the U.S. in 2019, a year had passed since the bookstore's closure, and the turmoil in his heart was gradually settling. He had temporarily left China to study political science at an American university. In his spare time, he wrote a series called “A Middle-Aged Father Goes to Study Abroad,” which was lighthearted and humorous, recounting only his personal experiences. When invited to give a speech at Harvard, he chose the theme of "education."

However, the education situation was becoming increasingly grim in China. Starting in 2017, the long- and short-term volunteer teaching programs Miao Yu had been advocating for were shut down. The local education department cited “educational sovereignty” issues, using qualifications review as a reason to force them to withdraw. The Baige Volunteers Trail in Shimenkan was also closed, reportedly for “religious reasons.” By 2023, Yu Miao himself had become a reluctant exile in the U.S., unable to return to his homeland.

Washington, D.C. is a city built on swampland. Dupont Circle is a large roundabout at the heart of the city. As one crosses the circle, there are homeless people on the lawns, as well as others sitting idly, watching pigeons and squirrels. Just beyond a Starbucks is Jifeng Bookstore. Its modest storefront, with green windows displaying Chinese and English books, stands next to Kramers Bookstore, a 70-year-old institution.

Here, Jifeng opened its doors, fitting right in, as if it had always belonged.

The three-story building, dating back to the 1920s, is part of a protected historical area. During renovations, strict guidelines had to be followed regarding load-bearing walls and storefront designs. Thankfully, Yu’s wife, Xiaofang, was there to help. Fluent in English and highly capable, she handled many of the tedious details, easing much of Yu’s burden.

With some trepidation, the bookstore’s official opening day arrived, and as readers poured in, Miao Yu realized that he wasn’t truly starting from scratch. Though forced to relocate to the U.S., Monsoon’s brand still had considerable pull. Almost everyone who came already knew of Jifeng.

Two days before the opening, Yu posted a message on WeChat: “Jifeng is reborn in a foreign land.” The post quickly went viral, but when it reached 70,000 to 80,000 views, it was deleted. Evidently, “Jifeng” was still considered a sensitive word by the authorities.

Yet, the enthusiasm of supporters exceeded Yu’s expectations. Many of the visitors had ties to Shanghai. In the store, Yu and Xiaofang often overheard familiar greetings: “Are you from Shanghai?”

On opening day, an elderly couple arrived. They had moved to the U.S. from Shanghai in the 1990s, and the husband, a university professor, had always made it a point to visit Jifeng whenever he returned to Shanghai. When the store was forced to close, it became a lingering regret. “This is something that brings tears to my eyes,” the old man said. When Yu Miao saw him again later, he had just finished an interview with The Washington Post, his eyes still moist with emotion.

Two women in their sixties, their hair fully grayed, walked in carrying suitcases. One of them pulled a book off the shelf—The Last Boat From Shanghai, a book about her mother. Her friend opened the book and pointed to a photo of a beautiful, elegant woman from 1948 Shanghai. That was her mother, who had left China for Taiwan. They were both delighted to find such a high-quality Chinese bookstore in the U.S.

That same day, a young man was searching for books he wanted. He explained that he and his wife had driven all the way from Ohio. His wife, a university professor, found many Chinese books she loved, treating them as treasures. Among her purchases was Xu Ben’s Humanity Under Totalitarianism.

Even phone calls started coming in. One caller said they were born in the U.S. and that their mother had spent most of her life studying Chinese history. She had passed away, leaving behind many Chinese books, but neither the caller nor their father could read Chinese. They asked if they could donate the books to the store.

Stories written on paper and stories of real lives converged in the bookstore, moving Miao Yu deeply. He felt that beyond the pursuit of knowledge, the bookstore carried a greater spirit: a longing for freedom and a desire for a normal, orderly life.

In the restrictive environment of China, Jifeng had embodied resistance, defiance, and an indomitable spirit. But in a normal society like this one, a bookstore existed to foster a better life and a more fulfilling order. Miao Yu was keenly aware of this shift.

In September 2024, just as Jifeng was reopening, The Economist published an article titled “Liberalism Is Far From Dead in China.” The article argued that despite intense repression, liberalism had not disappeared in China but had instead quietly gained more followers.

Jifeng’s forced closure, its “swan song” farewell, and its eventual rebirth overseas seemed to reflect the broader fate of civil society in China.

In 2018, poet Weitang Liao published an article in Taiwan’s The Reporter, expressing admiration for Jifeng’s well-curated selection of literary and liberal works. He compared Jifeng to First Line Bookstore in Shanghai 100 years ago, which had been shut down by the government for spreading leftist ideas. “Though today’s ideologies may be reversed, the root cause remains the same: fear of free thought. Only this time, there is no foreign concession in Shanghai to protect a bookstore.”

In 2023, Shanghai experienced lockdowns, the white paper protests on Urumqi Middle Road, and young people shouting, “We are the last generation.” Independent filmmakers documenting the protests were arrested. The pursuit of freedom trudges on through hardship, with everything coming at a cost. Since 1989, China’s prisons have never lacked prisoners of conscience. Human rights lawyers, independent journalists, NGO workers, artists, and countless ordinary citizens fighting for their rights—accompanying the severe setbacks faced by China’s civil society, this list grows ever longer. More people have been forced into exile, unable to return home.

From September 2022 until May 2023, Miao Yu was restless. During that time, he was living in Florida. The weather was scorching, but a coldness lingered in his heart. His wife, Xiaofang, had returned to Shanghai at the end of 2022 to care for her mother, enduring the three-month lockdown. When she tried to leave the country again, she was told she was barred from exiting. Chinese police suspected that an article critical of the government, published in the U.S., was linked to Yu. Shanghai officials demanded that Yu return for questioning, offering Xiaofang’s freedom as leverage.

What followed was nine agonizing months of persistent struggle, as well as media coverage by The Wall Street Journal, the Associated Press, and other major American outlets. Finally, in May 2023, Xiaofang was allowed to leave. Yu flew to New York to pick her up from the airport. While relieved, he also knew it would be difficult for him to return to China anytime soon.

In September 2023, shortly after moving to Washington, D.C., Yu was at a riverside gathering with friends. It was Mid-Autumn Festival, and as they watched the moonrise, someone remarked, “Everyone here is someone who can’t go back to China.”

As an exile, Yu Miao refused to wallow in nostalgia. He focused on what could be done, knowing that action often brings strength. During the most difficult days, he had waited with his children for Xiaofang’s return. “Now that she’s back, I fear nothing—not the failure of the bookstore, not anything that may happen in the future,” he said.

The bookstore was registered as a nonprofit, easing the pressure to turn a profit. With an open mind, Yu welcomed inquiries from all over about opening Chinese bookstores. He shared everything he knew, eager to see more connections between people—this, after all, was the essence of civil society.

“Here, there are no red lines for us. But we have our own bottom lines—academic integrity and social justice. We all know why we’re here, whether passively or actively,” he said. In Yu’s vision, striving for a better society in this place would carry values that could be transmitted back to his homeland. “No matter where you are, you have the right to pursue a better life and social justice,” he declared.

In September 2024, the Jifeng Cultural Forum hosted three lectures in Washington, D.C. On September 13, the second lecture was scheduled for 4 p.m., and readers had already begun to gather. Miao Yu and the bookstore staff moved aside bookshelves, while Xiaofang set up chairs. September is the most beautiful time of the year in Washington, with the heat retreating and the air comfortably mild.

That afternoon’s speaker was Minxin Pei, a political scientist who had left China after 1989 and had spent 40 years abroad. Now gray-haired, he spoke on “Privacy and Rights Under Digital Totalitarianism.” The previous day, Stanford University Professor Guoguang Wu had spoken on “Public Life and Ethnic Freedom: From ‘Sub-Exile’ to the Cultural Reconstruction of Overseas Chinese.” Neither speaker charged a fee, covering their own accommodations. They said they had come simply to show their support for Jifeng.

The bookstore was small, but the ceiling rose over four meters high. A projection screen was lowered at the entrance, turning the space into a lecture hall. The first floor was full, and from the second-floor window, one could see evening light, trees, and birds outside. The content on the screen, however, was gripping. Professor Pei introduced his new book, Sentinel China, detailing how China manages “key populations” and how the line system, interrupted during the Cultural Revolution, was rebuilt around 1974. Every page of the presentation addressed stark realities, and the 50 to 60 attendees were rapt with attention.

After the lecture ended, the chairs were folded away, but people lingered, unwilling to leave. Heated discussions continued, as if there was still so much left to say. This was precisely what Miao Yu envisioned a bookstore should be like.

In September, there were three lectures, including writer Ha Jin’s talk on “The Shackles of Homeland.” On October 6, the podcast Don't Understand was scheduled to hold an offline event here, featuring a conversation between independent scholar Xia Cai and writer Li Yuan. Each event was fully booked with eager participants.

“Every citizen—every free and equal citizen—has the right to demand fair treatment from the state. This is not a plea but a recognition of a fundamental right of all members of society. It is not charity, but the state's basic responsibility toward its citizens. When individuals become aware of this right and strive to defend it, the state cannot rely solely on violence to rule; it must provide reasons to win the people's support.”

This quote is from the new book Left-Wing Liberalism: The Ideals of a Fair Society by Professor Chow Po Chung of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Signed copies of the book were displayed on Jifeng’s shelves, and several copies sold in September alone.

I asked Miao Yu, “What has been your deepest impression during the period leading up to the bookstore's successful opening?”

“It feels like a stroke of luck. I don’t think I’ve done anything particularly great, but the response has been beyond anything I could have imagined. I think people identify not just with the Monsoon brand but also with concerns about China, the current era, and their own personal fate. There's a sense of shared vulnerability and frustration, which is what has sparked such a big reaction.”

“Do you still dream about returning to Shanghai? How would you describe your feelings toward China today?”

“We often talk about settling down, rooting ourselves in new soil, and starting a new life, but it's not that simple. Without realizing it, your emotions, your concerns, your hopes for the future—they are still tied to your homeland. It’s impossible that after just a few years, you can say you've fully started a new life. The ties that bind you are still there. Ha Jin's theme— ‘The Shackles of Homeland’—might never be fully resolved, not even in death. But you don’t have a choice. You have to struggle, step by step, to move forward.”

“Running the bookstore is also a kind of cleansing. Through this, you try to wash away your attachment to the past, to the homeland. You respond to it all with action, using action to resolve your inner turmoil. I hope that no day will pass by emptily.”

“Recently, people often talk about ‘the garbage time of history’ to describe an era where there seems to be nothing to do, a time of frustration. Do you accept this idea of historical garbage time?” I asked.

“Maybe history has garbage time, but for individuals, there is no such thing as garbage time! You can’t just stop doing things because you’re living through what history might call its garbage time,” he replied, quick and resolute. Then he added:

“I believe that one day, Monsoon will return. And we will all be free to go back and forth.”

Visit the JF Books website here: https://www.jfbooks.org/.

Jiang Xue (江雪) is an independent journalist in China, and the author of “Ten Days in Xi’an” (長安十日), an account of the month-long “zero-COVID” lockdown in Xi’an starting late 2021, the first major city lockdown since Wuhan in early 2020.

In 2008, when the 10-year lease of Jifeng Bookstore's Shaanxi South Road location expired, the landlord sought to increase the rent tenfold. In response, the media and cultural communities launched a “Defense Jifeng Store Battles.” In 2011, Jifeng’s Art Bookstore, Jing'an store, and Raffles City store closed down consecutively due to expired leases and increased rents that made renewal unaffordable. In 2012, when the renewed three-year lease for the Jifeng Bookstore on South Shaanxi Road expired with another rent increase from the metro company, Jifeng could not bear the costs. This led to the second “Defense Jifeng Store Battles.”

In 2008, after successive rent increases, Jifeng Bookstore faced its first crisis since its opening. The lease for its South Shaanxi Road location had ended. The property manager, Shanghai Metro, demanded a rent increase that nearly equaled the store’s entire revenue, rendering it unaffordable for Jifeng. Jifeng’s previous owner, Bofei Yan, in an interview later acknowledged that the metro company’s demand was not excessive; it aligned with the standard rates for commercial spaces on Shanghai’s Huaihai Road at that time. However, Jifeng Store could not afford the increase because the amount equaled the store’s entire revenue.

Jifeng’s other location in Shanghai, a community branch partnered with a café, was investigated for “selling books without a permit.” Despite formally applying for a “book retail license,” approval was denied, and the store was forcibly shut down by authorities.

The “September 13 Incident,” also known as the Lin Biao Incident, refers to the 1971 plane crash that occurred following a deterioration in relations between Chinese Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong and his deputy and successor, Lin Biao. This breakdown in relations began after the contentious debate over the position of State Chairman at the CCP’s Ninth Central Committee’s Second Plenary Session in 1970.

The "Project 571 Outline" was a draft document planned and written on March 23, 1971, by Lin Liguo, son of Lin Biao, among others. It outlined a military coup aimed at overthrowing then-Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, Mao Zedong. Following the Lin Biao Incident on September 13, authorities discovered this document, and with Mao's approval, it was distributed nationwide in 1972 as an official CCP document.

“The idea of ‘pure politics’ simply doesn’t exist,” this phrase once shared by Bofei Yan in an interview, captures a critical realization for his generation. Yan explained that youth at that time were steeped in propaganda painting Mao Zedong as a great leader, with Lin Biao as his loyal comrade, and the Communist Party as a noble, proletarian regime free from “internal conflicts.” However, the release of the “Project 571 outline” document, revealing Lin Biao’s plot to overthrow Mao, shattered this illusion, and showed that the Party’s internal dynamics were far from the “pure revolutionary camaraderie” they were led to believe. Instead, they were rife with political struggles. This revelation left Yan’s generation feeling deceived, exposing the reality that, contrary to their former beliefs, there was no such thing as “pure” politics devoid of self-interest and power plays—particularly under the Communist Party’s rule in China.

Zhongnanhai is a compound that houses the offices of and serves as a residence for the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party and the State Council.

The New Enlightenment, refers generally to a widely spread intellectual and social movement in 1980s China. This wave of thought, rooted in the “Discussion on the Criterion of Truth” during the period of “Boluan Fanzheng” (setting things right) in the late 1970s, is widely regarded as a continuation of the May Fourth Movement, marking a renewed call for ideological enlightenment. Against the backdrop of Reform and Opening-Up, the New Enlightenment of the 1980s emphasized a revival of the May Fourth ideals of “democracy” and “science,” along with an anti-Cultural Revolution, anti-feudal, and anti-traditional stance (cultural fever). It advocated for humanitarianism and universal values, including freedom, human rights, and the rule of law.

In 2008, Miao Yu participated in the “Xuan Zang Road” Gobi Desert Crossing, Stage B, known as “Ge-Three.” Shortly afterward, the “5.12 Wenchuan Earthquake” struck, prompting him and his Gobi teammates to establish the “Xuan Zang Road Volunteer Rescue Team.” Subsequently, he joined the team in delivering supplies, assessing situations, and offering comfort to the disaster-stricken areas. Following the Yushu Earthquake in April 2009, Mr. Yu and his teammates immediately traveled to the region to assist in relief efforts.